About Our 25th Anniversary Logo:

The Texas Master Naturalist Program has a fun way to award the volunteer hours we contribute: the annual service pin. Each one is unique to its calendar year, a “once in a lifetime” recognition to earn, own, and display. This tradition started in 2002 to recognize those Master Naturalists who completed 40 service hours and 8 hours of advanced training in that year. These pins have their own symbolism beyond the hours accrued for service. They represent inhabitants and habitats from around the ecological regions of Texas.

For our 25th Anniversary Celebration, the logo was created featuring 14 of the species that have been used for recertification pins in previous years. Each species is associated with its ecoregion, which is the subject of the 2023 recertification pin. If you are interested in learning more about our certification pins, you can visit https://txmn.tamu.edu/chapter-resources/certification-service-pins/ to learn more.

The 25th Anniversary Logo was created by Audrey Taulli, whose work can be found on Instagram with the username @alht.studio. We are excited to share her design!

Species Descriptions from the 25th Anniversary Design can be found below:

Lindheimer Daisy – 2003 Service Pin

The Lindheimer daisy (Lindheimera texana) is a member of the Asteraceae family. The common name, Texas yellow star, or just Texas Star daisy is derived from the yellow flowers that have five petals corresponding to the five points of the Texas Lone Star emblem. The scientific name honors the Father of Texas Botany, Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer. He is credited with the discovery of several hundred plant species and subspecies; forty-eight of those carry his name. A reseeding, native wildflower, this daisy is found throughout all of Texas, north into Oklahoma, east to Arkansas and Louisiana, and south into Mexico. As a winter annual that requires full sun, little water, and prefers well-drained sandy loam or limestone soils, the Lindheimer daisy has a 6 inch to 2-foot-tall single stem with long, bright-green leaves crowded along it. The time to plant this daisy is in the fall. Appearing in late winter, it will initially grow slowly. However, once February arrives, it will be one of the first wildflowers to cover the countryside! It blooms by March and continues throughout April and May. Once established, this beautiful wildflower will reseed freely.

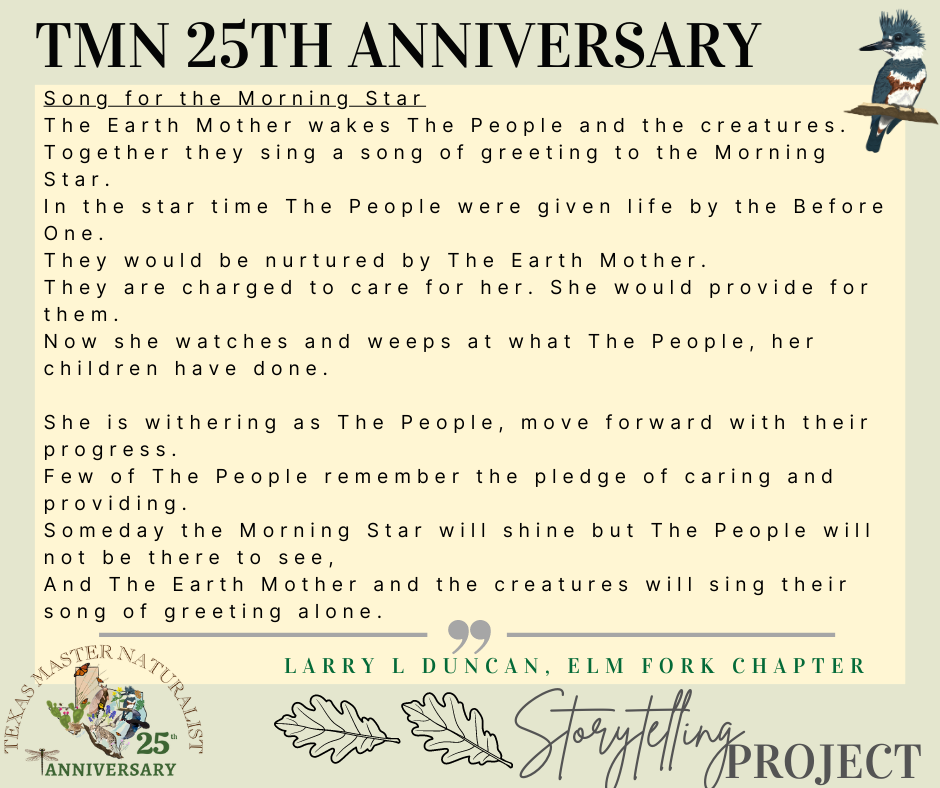

Belted Kingfisher – 2005 Service Pin

Hovering high above the water to spot a fish, then plunging headfirst in a swift direct line to catch it, the belted kingfisher demonstrates its unique style of hunting. As a sit-and-wait piscivore predator, these medium- sized birds often perch conspicuously on branches with a clear view over their feeding territories. They are easily distinguished by their large heads, blue-and-white plumage, and long, stout bill. Announcing its presence with a loud, staccato rattling cry that allows it to be heard before it is seen, the belted kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon), was our 2005 service pin. Its name describes the belt of blue-gray feathers across its white breast. This is one of the few bird species in which the female is more colorful than the male. She has a chestnut strip extending across her belly and under her wings, while the male displays a plain white underbelly. Texas has three species of kingfishers. Although you won’t find many together at one time, it is one of North America’s most widespread and abundant land birds, and the global population is estimated at 1.7 million individuals. We are very fortunate that this remarkable bird is a part of our beautiful Texas natural landscape.

Texas Prickly Pear – 2006 Service Pin

In 1995, a Texas House resolution named this special shrub as our Texas state plant. The Texas prickly pear cactus (Opuntia engelmanni var lindheimeri) scientific name is a tribute to the man who first documented this species, Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer, the Father of Texas botany. The adaptable prickly derives its name from its numerous leaves that harden into sharp spines as they age. It can survive under many different environmental conditions, and can easily be propagated from seeds and cuttings. Interestingly, although it is nearly 90 percent water by weight, every part of the prickly pear is edible. People eat it, bees go wild for the pollen, and it provides cattle and other livestock a reliable food source during the late summer heat when many other plants are struggling. Tunas, the reddish-purple fruit, ripen from July to September. They contain a sweet juice and are eaten raw or processed into preserves, syrups, and fermented juice, often compared to watermelon. Nopales—the branches or pads of the plant—are eaten as a vegetable with a taste like green beans or okra when cooked. Put simply, this unique Texas plant offers value for its nutrition and visual splendor across our vast and beautiful Hill Country landscape.

Texas Purple Sage – 2008 Service Pin

The Texas state legislature’s 2005 designation declared the Texas purple sage as our official native shrub. Also known as cenizo, Texas silverleaf, barometer bush (because after a good rain it explodes with hundreds of small purple flowers), and Texas ranger, this plant grows naturally on the Edwards Plateau, in the Southwest Texas Plains, and westward in the Trans-Pecos. As a native, evergreen, medium-sized shrub, Texas purple sage provides forage for cattle and a nesting place for songbirds, including our state bird, the mockingbird. It also provides essential stabilization to desert soils as it grows along hill slopes. Commonly growing to about five feet tall, it can mature to eight feet in height and spread just as far horizontally. While the grayish-green woolly leaves are not terribly spectacular, this sage produces copious amounts of beautiful lavender flowers. Texas purple sage is truly a native landscaper’s plant of choice. This plant is full-sun, drought tolerant, deer and pest resistant, has few disease issues, and does not need fertilizing. It is also considered to be one of the best plants for attracting butterflies. Although watering in dry summer months will make it grow faster, overwatering or poor drainage will quickly kill it. In a land that waits for the rain, we are rewarded afterward with the surprising, magnificent blooms of the Texas purple sage!

Wood Duck – 2010 Service Pin

The genus Aix or “perching ducks,” unlike most ducks that nest on the ground, build their nests high in trees and often over water. This duck that many Texans love is the wood duck (Aix sponsa). The scientific name, meaning “betrothed duck,” features the boldly patterned, brightly colored males with their green heads, red eyes, purple breasts, and white throats. It is clearly a favorite of hunters, constituting more than 10 percent of the annual waterfowl harvest in North America. As an omnivore that enjoys seeds, fruits, and insects, the wood duck nests in riparian habitats. Its preference for elevated nest sites has the advantage of protecting young ducks from predators. The ducklings use their sharp claws and a special tooth on their beak—two unusual traits among ducks—to climb out of the nest cavity and jump to the ground. Some fall hundreds of feet without injury! The wood duck was abundant in North America in the 1700s. The population declined seriously during the late 1800s because of our overharvesting of timber, drainage of marshes, and excessive exploitation by humans for its meat and feathers. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 protected it from harvest until 1941, and a series of game restrictions enhances that protection today. Legislation, extensive habitat restoration across its range, and the erection of thousands of nest boxes to replace lost natural cavities in wetland habitats helped the population make a remarkable comeback. The recovery of the wood duck to healthy numbers is a dramatic success story in the history of American wildlife management.

Texas Horned Lizard – 2011 Service Pin

In 1993, the Texas horned lizard (Phyrnosoma cornutum) was designated the official state reptile. Horned lizards are often called horny toads or horned frogs, although they are not amphibians. They are reptiles with scales, and they produce their young on land. As mentioned, conservation is very important for our horned lizard because they are at risk throughout their normal range due to habitat loss, illegal collection, and the imported fire ant, which kill their hatchlings and out-compete their food sources. A 1967 law bans the collection, export, and sale of horned lizards. The Horned Lizard Conservation Society now partners with ranchers and landowners to protect them. At about 3½ to 5 inches long, horned lizards are found in arid habitats with sparse plant cover. Because they dig for hibernation and nesting, they are commonly found in loose soils. They feed primarily on harvester ants by quickly snapping them up with a flick of the tongue. Preyed upon by various birds, reptiles, and mammals, Texas horned lizards have some amazing defenses. They most effectively avoid predators by simply holding still, letting its coloration help blend into sparse vegetation. It is also renowned for its ability to shoot a stream of blood from its eye (its eyelid) potentially confusing a predator and allowing it to escape. Don’t mess with Texas horned lizards!

Mexican Free-Tailed Bat – 2012 Service Pin

The Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) is our Texas state “flying mammal.” This insectivorous mammal leaves its roost in caves or bridges near water around sunset to forage for flying insects, which they catch in flight using echolocation. It is estimated that a typical colony of bats can consume 250 tons of insects every night, saving farmers millions of dollars without the use of pesticides. These bats form very large colonies, including the Bracken Cave population near San Antonio, which is the largest congregation of wild mammals in the world. The Mexican free-tailed is the most common species of bat in the southwest. Living as long as 18 years, they are highly migratory, spending fall and winter in Mexico and returning to the southern United States in spring. Mexican free-tailed bats have some notable physical characteristics, weighing in at about half an ounce with a wingspan around one foot. These beautiful animals are the fastest mammals on earth, clocking in at 99 mph in level flight. Mexican free-tailed bats are the jets of the bat world! They are called “free-tailed” because their tails extend more than one third beyond the tail membranes (the rear “wing-like part” between their hind legs), while most other bats have tails that are completely enclosed within the tail membranes.

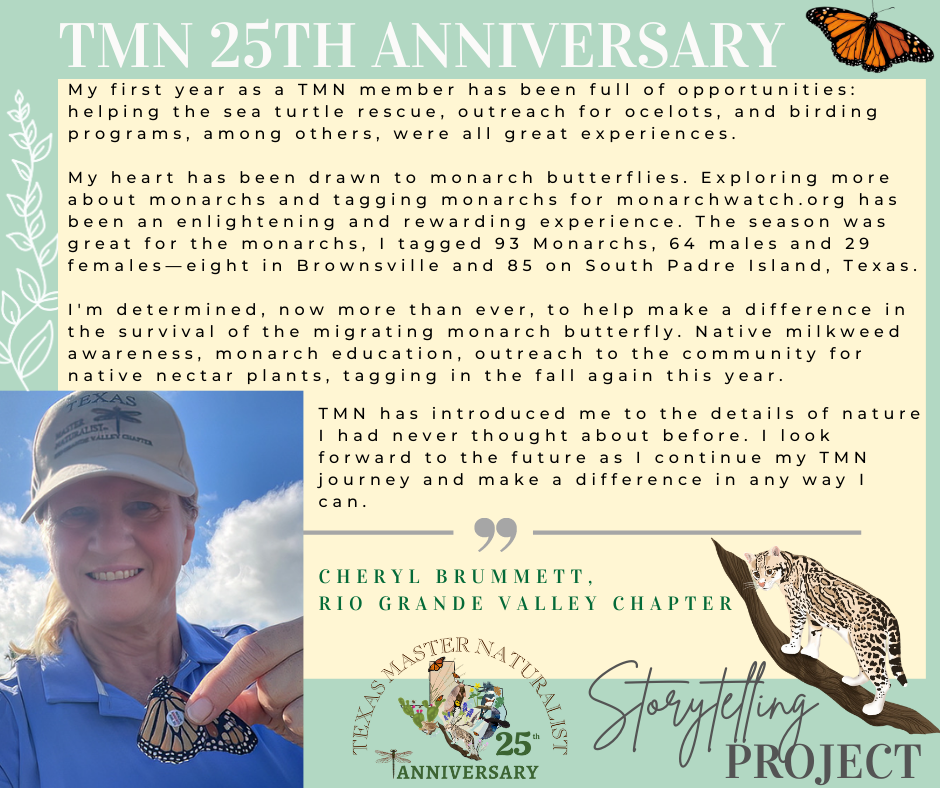

Monarch Butterfly – 2013 Service Pin

In 1995, this iconic insect, Danaus plexippus (Greek for “sleepy transformation” or chrysalis), was named the Texas state insect. Over the last 30 years, the population of these important insects has fallen dramatically and prompted a petition to the US government to add it to the Endangered Species Act. A contributor to the decline of the monarch is the loss of habitat, including the loss of milkweed across northern regions of the monarch’s migration flyway. Planting milkweed in your yard or garden will help increase their numbers as both a place for females to lay their eggs each as well as a food source for the caterpillars which often eat up to 200 times their weight in leaves! In 2015, San Antonio became the first “Monarch Champion” city by signing the National Wildlife Federation Mayor’s Monarch Butterfly Pledge. The city provides migratory support through gardens and nesting areas such as the work being done by the Hardberger Park Conservancy and at the San Antonio River Authority’s King William Reach pollinator garden.

Nine-Banded Armadillo – 2014 Service Pin

The 1995 legislative resolution declaring the official state small mammal, shows that these traits are shared by the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). This armadillo, or “little armored one” in Spanish, is the only species of twenty armadillos worldwide that lives in the United States. Polyembryony, the process through which multiple embryos develop from a single fertilized egg, allows the armadillo to give birth to identical quadruplets every time! After being weaned from their mother at three to four months, the armadillo typically lives between seven and twenty years. Nocturnal and mostly solitary, armadillos live in forested or grassland habitats. Each armadillo may have up to ten burrows within its home range that varies from one to twenty-two acres. To cross a river in their range, they swim after increasing their buoyancy by swallowing air, or just sink and walk across the bottom while holding their breath for up to six minutes! They forage by smell in a slow wandering pattern and are easy for us to sneak up on. Armadillos are known to eat over 500 different foods, but most of their diet consists of invertebrates such as beetles, ants, and grubs. Their bony body covering plates, called scutes, help protect them from predatory mountain lions and bears. An additional defense is leaping vertically before quickly running away. This tendency to jump when startled often leads to their demise on highways. Although many are killed each year, there is a large population of armadillos in our state, and they are not endangered.

Bluebonnet – 2015 Service Pin

In 1901, the Texas bluebonnet (Lupinus texensis) became the Texas state flower. The bluebonnet was also our 2015 service pin, offered in celebration of this beautiful wildflower that blooms from late March to early May. Subsequently, in 1971, the Texas Legislature declared that any similar species of Lupinus are also state flowers, so officially there are currently six state flowers in Texas. Meanwhile, thanks to Lady Bird Johnson, Texas became the first state to beautify our highways by planting flowers. Bluebonnets are a drought-tolerant plant that need at least 8-10 hours of direct sunlight. September and October are the months for planting so they can develop a strong root system during winter. The white buds on the tip of some stems gave it the nickname of El Conejo (the rabbit) because it looks like a bunny tail. One defense that bluebonnets do have toward animals is toxicity. Deer do not like their taste and will avoid them. If ingested, bluebonnets are poisonous to humans, so be very careful to keep them out of the reach of small children when you’re out taking your springtime photos.

Ocelot – 2018 Service Pin

There were 200 percent more Texas Master Naturalist service pins earned by Alamo Area Master Naturalists in 2018 than there are wild ocelots alive in Texas! 154 pins were earned by Alamo Area Chapter Members and just 50 ocelots in Texas. The ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) is an elusive, solitary, non-migrating species and one of only five wild cats that call Texas home. Nicknamed the phantom cat of the chaparral for placing its den in the densest part of a thorny thicket, the ocelot is similar to the bobcat. However, it is distinctively different with its unique “chain rosette” spotted coat, long ringed tail, and slightly rounded ears. As nocturnal hunters, ocelots prey on small vertebrates found in their one to eighteen square kilometer home range. Breeding in late summer, they normally raise litters of just two to three kittens. Healthy ocelots can live from eight to eleven years. Endangered within the U.S. since 1982, historical records indicate their previous habitat extended from the Edwards Plateau to the Gulf Plains. Decline is primarily due to habitat loss and being prized for its pelt. Ironically, throughout the remainder of its range in Latin America, it is often the predominant predator and is considered abundant. The real hope for saving the ocelot in Texas lies with private landowners and one public location, the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge near Brownsville, which proudly hosts one of only two breeding populations left in the United States.

Golden-Cheeked Warbler – 2019 Service Pin

The golden-cheeked warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia) is a small, brightly-colored songbird with a big reputation. To warble, is to sing. In appearance, they are approximately four to five inches in length and best known for their brilliant yellow face with a black stripe through the eye. As they migrate to Texas near mid-March from their winter homes in Central America and Mexico, birdwatchers from around the world travel to our Hill Country for a mere glimpse of this rare songbird. Every one of them is truly a native Texan; it is the only bird species of nearly 360 that find their mate here that breed exclusively in Texas. The abundance of Ashe juniper (cedar) spread across thirty-six counties of the Edwards Plateau and Balcones Escarpment is the specific tree that hosts their nests in the foliage. In 1990, they were placed on the endangered species list due to the destruction of its breeding range by suburban development. It is estimated that only 27,000 survive today, a decline of about 25 percent in the last thirty years. Some local areas set aside to help protect them include Balcones Canyonlands, the Bull Creek Nature Preserve, Cibolo Bluffs Preserve, and the backcountry of Government Canyon State Natural Area. The golden-cheeked warbler is one of nature’s most beautiful animals and a vital asset to both local ecology and our heritage. Hopefully, someday we will all get the chance to see them in the wild.

American Bumblebee – 2020 Service Pin

These large fluffy insects provide a substantial ecological contribution as preeminent pollinators. The Department of Agriculture even places the estimated value of native bee pollination on America’s farms at three billion dollars annually! In Texas, we have nine different bumblebee species, and the American bumblebee, Bombus pensylvanicus, is native to Texas. It can be identified by the single yellow moon-shaped marking on its thorax, the center of the three sections of the bee. Like most bees, American bumblebees are highly social, living in colonies with a social caste where everyone has a specific task. The caste consists of the queen, female workers, and males. A well-nourished bumblebee colony can reach a population size of 300 to 600 workers. In comparison to honeybees, this is quite small; honeybee hives contain thousands of bees. Unfortunately, the American bumblebee was designated as one of thirteen hundred Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the Texas Conservation Action Plan (2012). The recent decline in bumblebees is creating renewed interest in their purpose, well-being, and future.

Sideoats Grama – 2021 Service Pin

Grasses are often taken for granted, but they are the most important plant group, as grasses make up the world’s most significant food source. Grasses occupy all parts of the earth and exceed any other plant. There are more than 10,000 varieties worldwide and nearly 1,400 in the United States. Grasses make up about 26 percent of earth’s plant life. Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) is a native, bunchy grass, designated by legislative proclamation in 1971 as the official state grass of Texas. Taking its name “sideoats” from the oat-like dried seed spikelets found on one side of the stem or stalk where the flowers were, and the Latin grama for grass, sideoats grama is a perennial warm season grass that photosynthesizes most efficiently during hot summer days. It is found throughout Texas, especially in the Blackland Prairies, Edwards Plateau, and the High Plains. On the rangelands of West Texas, sideoats grama is the backbone of the ranching industry, producing a nutritious forage relished by all classes of livestock and wildlife. Sideoats grama is used extensively across Texas to reseed depleted grasslands for conservation purposes.

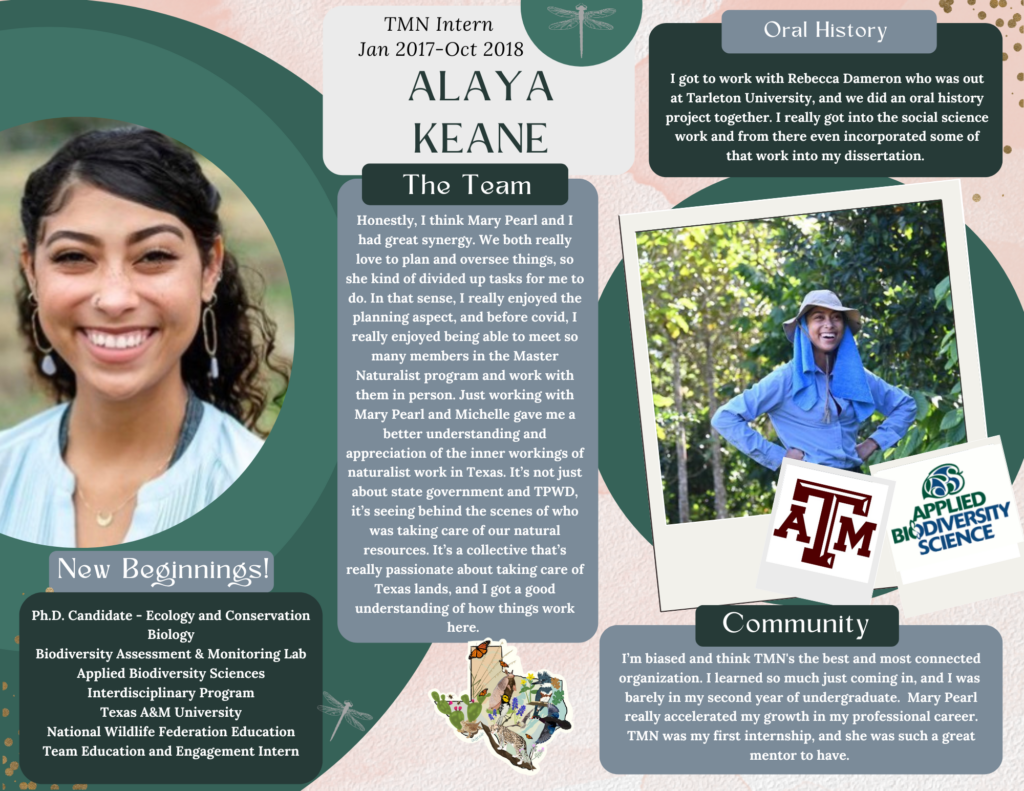

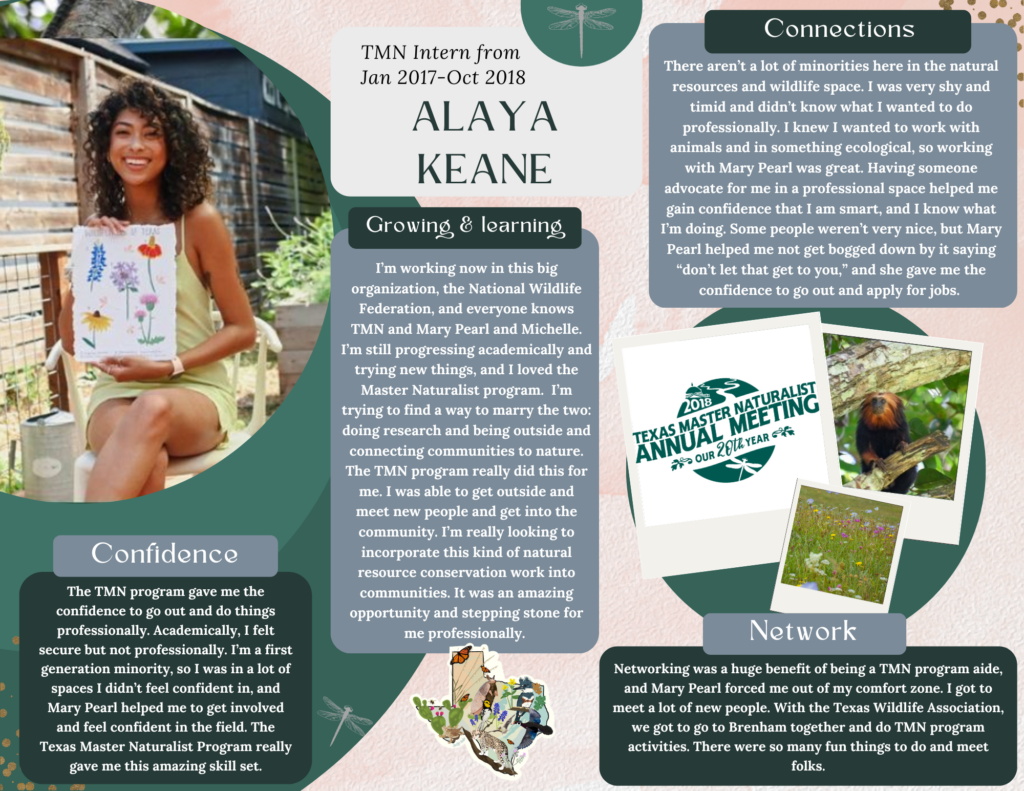

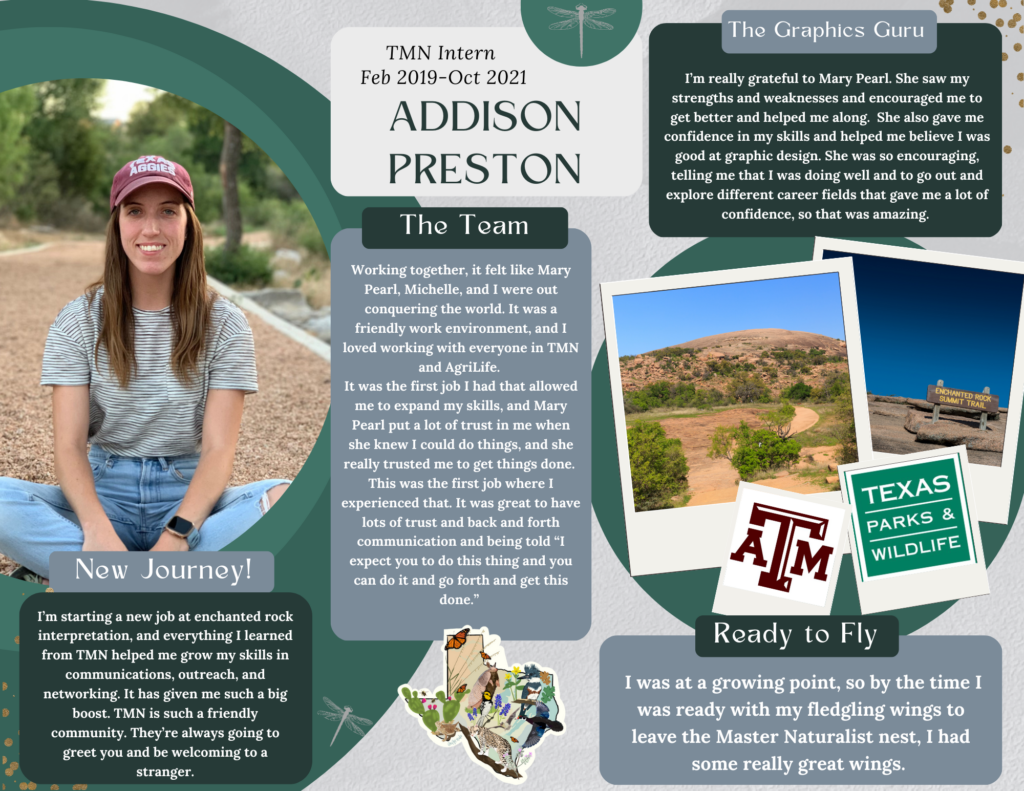

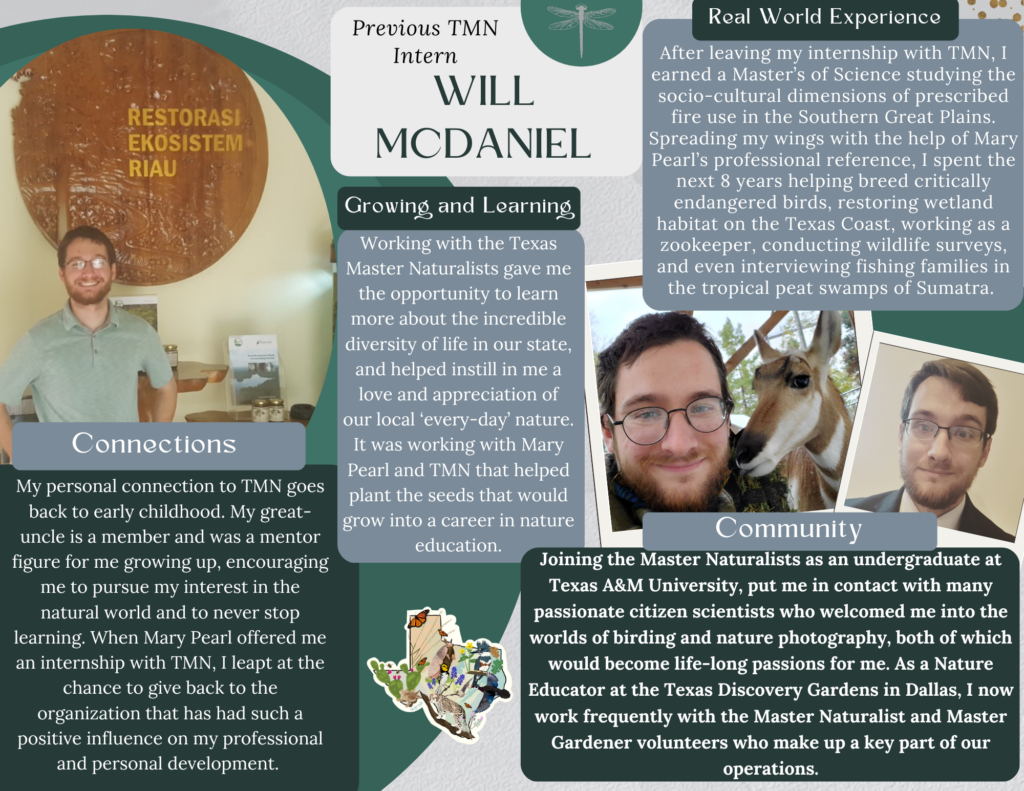

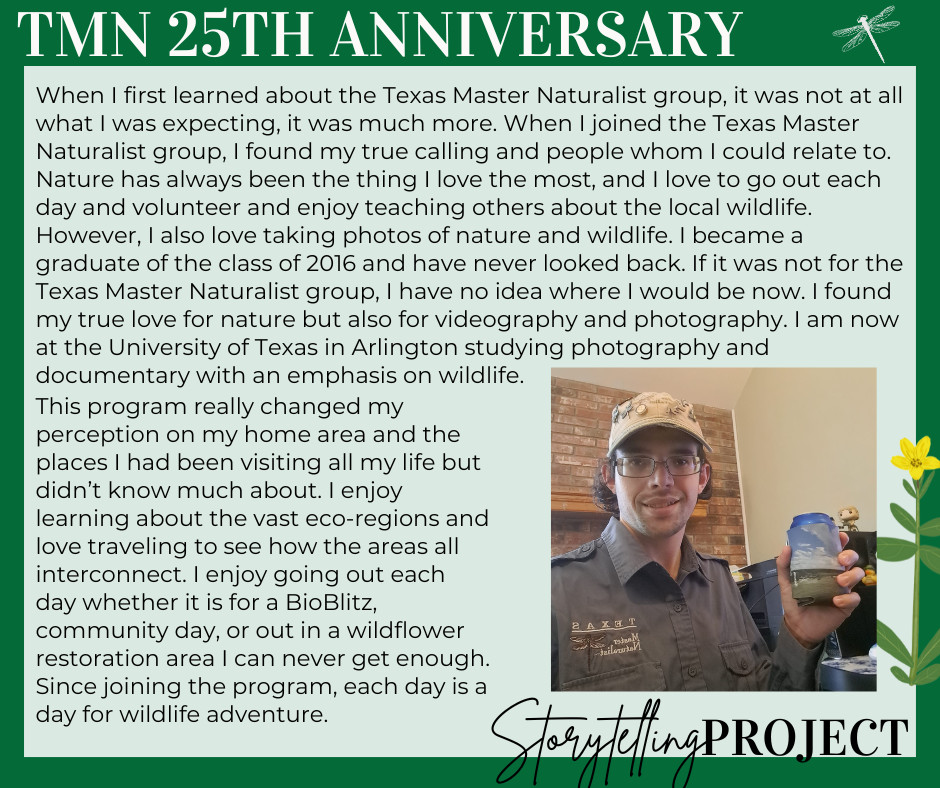

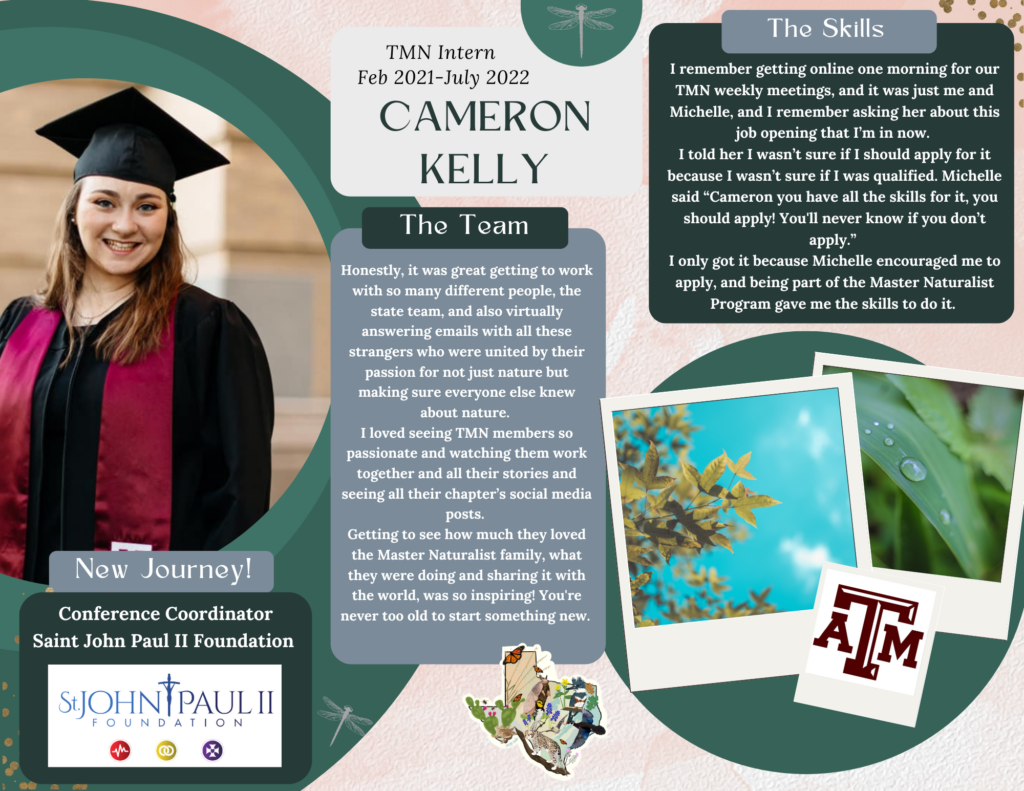

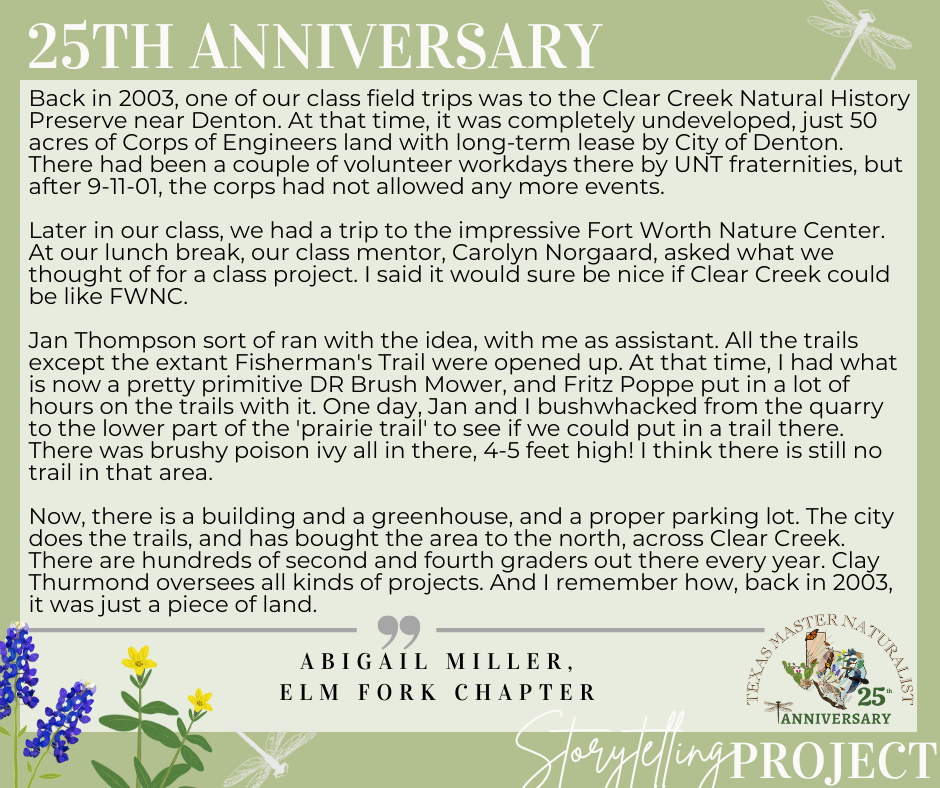

Storytelling Project

To celebrate our 25th Anniversary, we are hosting a year-long storytelling project to highlight our wonderful TMN members and their conservation volunteer work across the state.

We want to know! What inspired you to became a TMN member? Do you have a favorite TMN in-the-field memory? What has been your most meaningful project, community outreach, or conservation event? What does nature mean to you? Use these questions as inspiration for your creative brainstorming or feel free to use them as a direct prompt.

You’ll have two options to share your experiences as a Master Naturalist: either through video or words (written story and/or poetry). Please choose one format per story. You’re welcome to share more than one story if you’d like to try each format (just submit the form again!). To send us your story, please fill out the form below.

Tips on writing down your experiences:

- Find a nice quiet place to write and let your ideas flow out onto the page for a few minutes without self-interruption.

- When you’re ready to put on your editor’s hat don’t forget to spell check your work.

- Keep stories short and sweet, for example no more than 1 page in Word/google doc.

Tips on taking a great selfie video:

- Be sure to wear your favorite TMN regalia (hats/patches/t-shirts/sweaters etc.) when recording.

- Find a nice nature spot outside for a backdrop.

- Notice what sounds and noises surround your spot. Try to avoid, if possible, any sounds that may make it difficult for the microphone to catch your words (for example traffic noise and/or windy days).

- Have a good light source. When outside, mornings and evenings can give you a nice soft light good for videos.

- If it helps you to stay on track, write down your thoughts before recording and have your notes close at hand.

You’ll be able to find the stories on the Texas Master Naturalist state website and our social media channels throughout 2023. Thank you for all you do this year and every year as a Master Naturalist volunteer!

Your Stories: